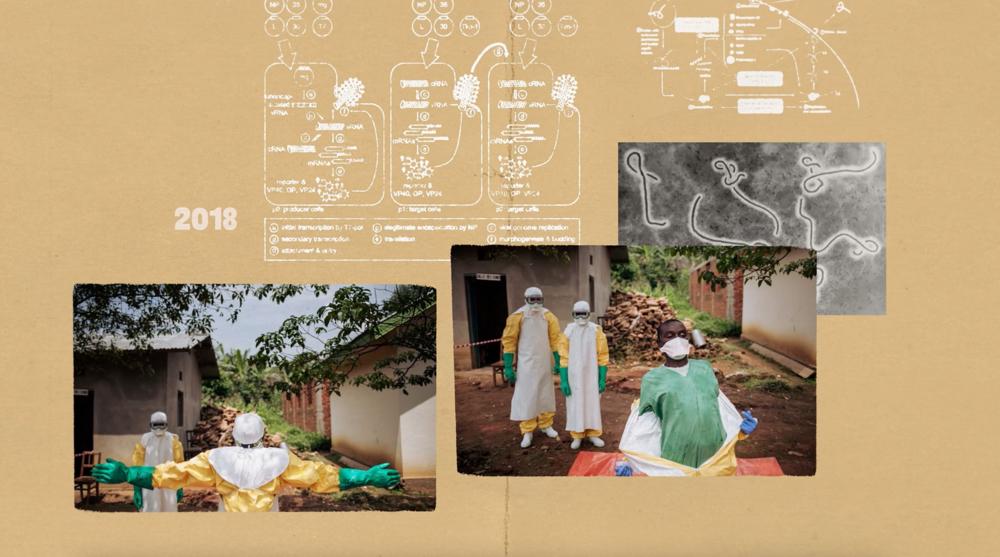

MSF calls for emergency stockpile of Ebola treatments ten years after world’s deadliest outbreak

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

Alors que le monde célèbre les dix ans de l'épidémie la plus meurtrière de la maladie à virus Ebola, qui a tué plus de 11 000 personnes en Afrique de l'Ouest en 2014, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) regrette que, bien qu'il existe désormais deux traitements approuvés contre Ebola, ils ne soient pas facilement accessibles à travers un stock d'urgence prêt à être utilisés dans les endroits où ils pourraient être nécessaires lors d'une future épidémie.

As the world marks ten years since the deadliest Ebola virus disease outbreak that killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is disappointed that while two approved Ebola treatments now exist, they are not readily available via an emergency stockpile for use in places where they would likely be needed in a future outbreak.

The treatments remain under the exclusive control of just two US pharmaceutical corporations, Regeneron and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, and almost all the treatments currently available worldwide are kept in a national security and biodefense stockpile held for use by the United States. There is therefore a need to set up an international emergency stockpile of these treatments supplied by Regeneron and Ridgeback, and run by the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision, to ensure the treatments can always be provided at short notice to anyone, anywhere who needs them.

Ten years ago, the world was not prepared for the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in West Africa. There were no antiviral treatments, and this made it hard to convince sick people to come to the treatment units. There were no vaccines, and so protecting people was limited to trying to convince them to change their behaviour, which years of experience has taught us takes time and often has limited success. This made it difficult to control the outbreak,” said Dr Armand Sprecher, Public Health Specialist at MSF.

After nearly half a century without any specific treatments, it was only during the largest outbreak of Ebola in 2014, when wealthier countries were confronted with the threat of Ebola reaching their borders, that funding for the research and development of Ebola treatments and vaccines increased dramatically. Then, after a combination of over US$800 million in public funding and essential contributions including from affected country governments, NGOs, and academic institutions, which hosted or facilitated clinical trials, as well as patients and survivors who directly participated in testing the treatments, two treatments were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2020. These treatments were recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, and are now included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. There are now also two vaccines, which – alongside treatment – are essential to preventing and responding to an Ebola outbreak. While a significant addition to the Ebola response toolkit, these new medical tools only respond to Zaire ebolavirus, the most common species of virus which caused the 2014 outbreak.

The treatments – REGN-EB3 (atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab), marketed by Regeneron as Inmazeb, and mAb114 (ansuvimab), marketed by Ridgeback as Ebanga – remain largely inaccessible to the people who need them during outbreaks.

While there are many challenges to the rapid deployment of treatments in an Ebola outbreak, the fact that only one third of patients received either treatment in five outbreaks since 2020 is, in large part, due to the treatments not being readily available where outbreaks most often occur. Regeneron and Ridgeback retain private control of these treatments through patents and licensing, and almost all available treatments are held and controlled by the US.

One clear lesson learned from the past ten years is that relying only on the goodwill of private corporations or governments is not the solution to an access-to-medicines problem,” said Dr Márcio da Fonseca, Infectious Disease Advisor for MSF’s Access Campaign.

In addition, MSF urged all patent holders of Ebola treatments to issue licenses and transfer the technology to capable manufacturers so that more producers can make Ebola treatments, as this will help increase their availability in the future.