Luxembourg Guerre Gaza-Israël

Guerre Gaza-Israël

Ukraine

Ukraine Soudan

Soudan Haïti

Haïti

After a year of war in Sudan, a rapid scale up of response is needed to avoid catastrophe

After one year of war, the aid provided to millions of people is a drop in the ocean due to political blockages created by the warring parties and lack of action from the United Nations and international humanitarian organisations.

Haiti Testimonies

Testimonies

"The situation in Port-au-Prince today is a humanitarian crisis and it demands an urgent response"

Dr. Priscille Cupidon, medical activity manager of the MSF urban violence project, which runs mobile clinics in violence-affected neighborhoods of the city, describes the impact of violence on health and health care workers in Haiti.

NigeriaTestimonies

Surviving pain and fear: Women’s harrowing tales from camps in Benue

After receiving reports of alarming levels of sexual violence against women and girls in the camps around Makurdi, the capital of Benue state, MSF is providing survivors with medical and psychological care.

Gavi: the future five-year strategy must guarantee equitable access to vaccines

With routine vaccination efforts failing to reach people in fragile and emergency settings, MSF is seeing low vaccination coverage and more outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, like diphtheria and measles

GreeceAll news

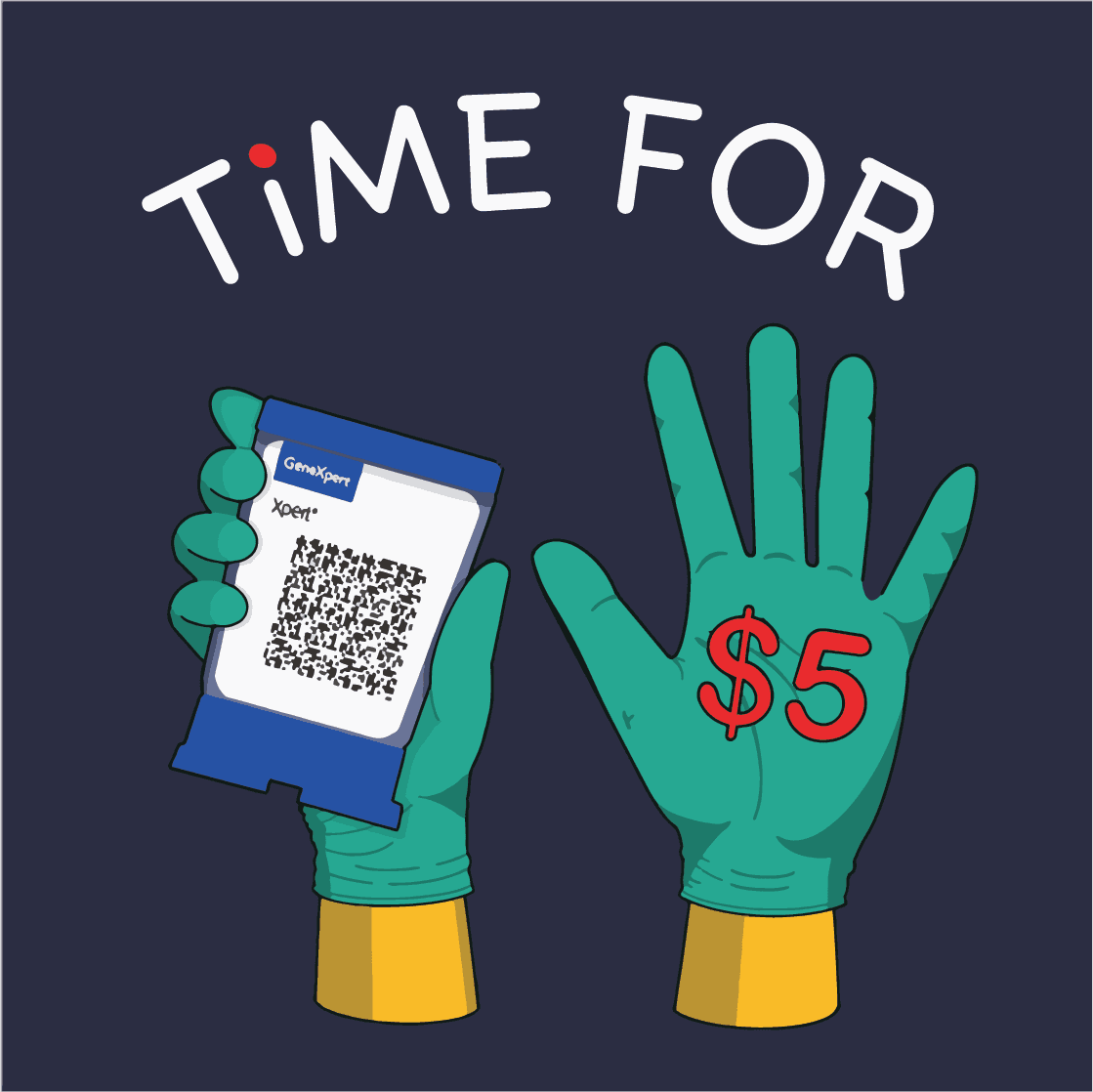

Bring the GeneXpert’s costs down to 5 dollars: new supporting evidence

A recent study by the MSF's Athens Day Care Centre project and LuxOR highlights the importance of affordable Point-of-Care Diagnostics for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections.

MyanmarTestimonies

Q&A with MSF’s project coordinator for northern Rakhine, Nimrat Kaur

Myanmar is facing an acute humanitarian crisis since fighting escalated at the end of October 2023. Nimrat Kaur has been the project coordinator in Maungdaw since mid-April 2023.

Democratic Republic of the CongoAll news

Walikale, North Kivu: a “Host Village” to prevent maternal and infant mortality

Every month, around 30 women with high-risk pregnancies, many from remote or isolated villages without proper healthcare, come to give birth in the “Village d’Accueil” at the Walikale general reference hospital (DRC).

MozambiqueTestimonies

In Mogovolas, clean and safe water for Bilharzia-free living – Mozambique

In the northern region of Mozambique, specifically in Mogovolas district, where the prevalence of Bilharzia is notably high, access to clean water becomes a genuine suffering.

Ukraine Emergency All news

All news

MSF Condemns Missile Attack that Destroyed its Office in Donetsk Region

MSF strongly condemns the missile attack on its office in Pokrovsk. The building was destroyed completely and five people were injured, including MSF’s security staff. As a result, MSF has suspended its activities in the Donetsk region temporarily.