Luxembourg Guerre Gaza-Israël

Guerre Gaza-Israël

Ukraine

Ukraine Soudan

Soudan Haïti

Haïti

After a year of war in Sudan, a rapid scale up of response is needed to avoid catastrophe

After one year of war, the aid provided to millions of people is a drop in the ocean due to political blockages created by the warring parties and lack of action from the United Nations and international humanitarian organisations.

Haiti Testimonies

Testimonies

"The situation in Port-au-Prince today is a humanitarian crisis and it demands an urgent response"

Dr. Priscille Cupidon, medical activity manager of the MSF urban violence project, which runs mobile clinics in violence-affected neighborhoods of the city, describes the impact of violence on health and health care workers in Haiti.

GreeceAll news

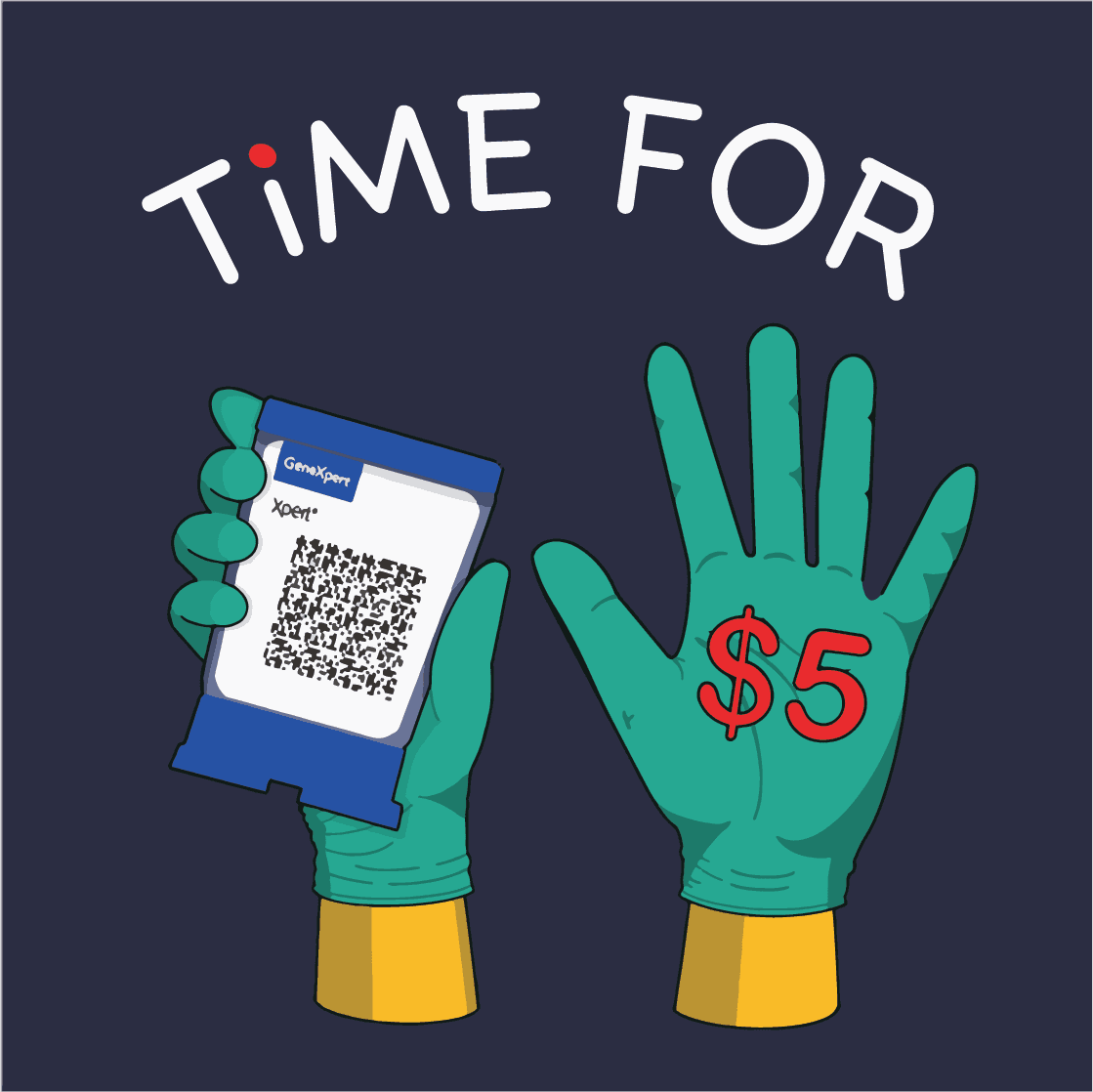

Bring the GeneXpert’s costs down to 5 dollars: new supporting evidence

A recent study by the MSF's Athens Day Care Centre project and LuxOR highlights the importance of affordable Point-of-Care Diagnostics for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections.

MyanmarTestimonies

Q&A with MSF’s project coordinator for northern Rakhine, Nimrat Kaur

Myanmar is facing an acute humanitarian crisis since fighting escalated at the end of October 2023. Nimrat Kaur has been the project coordinator in Maungdaw since mid-April 2023.

Ukraine Emergency All news

All news

MSF Condemns Missile Attack that Destroyed its Office in Donetsk Region

MSF strongly condemns the missile attack on its office in Pokrovsk. The building was destroyed completely and five people were injured, including MSF’s security staff. As a result, MSF has suspended its activities in the Donetsk region temporarily.

Democratic Republic of the CongoAll news

Walikale, North Kivu: a “Host Village” to prevent maternal and infant mortality

Every month, around 30 women with high-risk pregnancies, many from remote or isolated villages without proper healthcare, come to give birth in the “Village d’Accueil” at the Walikale general reference hospital (DRC).

Ready to map with us? See you on May 22, 2024!

Would you like to help MSF while remaining in Luxembourg? Support our teams in the field from a distance? You can do so by taking part in our next mapathon, to be held on May 22, 2024 at Unipop.

War Gaza-Israel

All news

All news

Gaza: How the Israeli army besieged and attacked Nasser hospital

On the night of 14 to 15 February 2024, Nasser hospital, once the largest hospital in southern Gaza, was shelled by Israeli forces. The orthopaedic department was hit, killing one person and injuring eight others

MozambiqueTestimonies

In Mogovolas, clean and safe water for Bilharzia-free living – Mozambique

In the northern region of Mozambique, specifically in Mogovolas district, where the prevalence of Bilharzia is notably high, access to clean water becomes a genuine suffering.