Luxembourg Guerre Gaza-Israël

Guerre Gaza-Israël

Soudan

Soudan Haïti

Haïti

After a year of war in Sudan, a rapid scale up of response is needed to avoid catastrophe

After one year of war, the aid provided to millions of people is a drop in the ocean due to political blockages created by the warring parties and lack of action from the United Nations and international humanitarian organisations.

Haiti Testimonies

Testimonies

"The situation in Port-au-Prince today is a humanitarian crisis and it demands an urgent response"

Dr. Priscille Cupidon, medical activity manager of the MSF urban violence project, which runs mobile clinics in violence-affected neighborhoods of the city, describes the impact of violence on health and health care workers in Haiti.

Ukraine EmergencyAll news

War-torn Minds: Navigating Mental Health Issues Amid War in Ukraine

MSF's mental health programme, a key component of the response in Ukraine, has helped the staff of the Trostianets hospital to cope with the horrors of war.

KenyaAll news

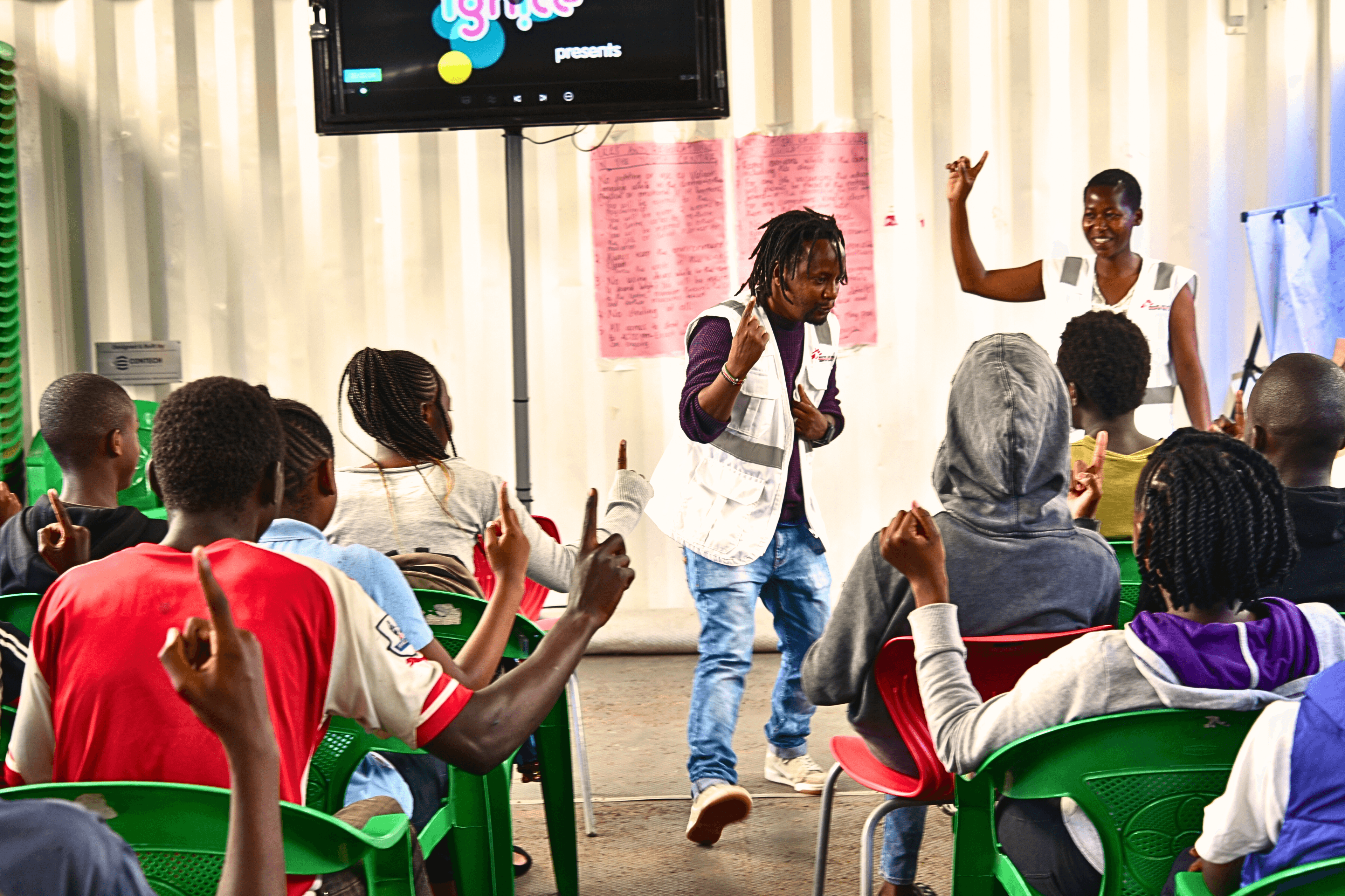

Beyond medical care: Dandora Youth Friendly Center, a safe space for young people from Nairobi's disadvantaged neighborhood

The Dandora Youth Friendly Center serves as a safe space for young people between ages 10 to 24, offering more than just medical care. This vulnerable population grapples with urban violence, substance abuse, and socio-economic challenges.

Charges against rescues at sea dropped: Saving lives is not a crime

Seven years of falsehoods swept away, but attacks continue.

NigeriaTestimonies

Surviving pain and fear: Women’s harrowing tales from camps in Benue

After receiving reports of alarming levels of sexual violence against women and girls in the camps around Makurdi, the capital of Benue state, MSF is providing survivors with medical and psychological care.

GreeceAll news

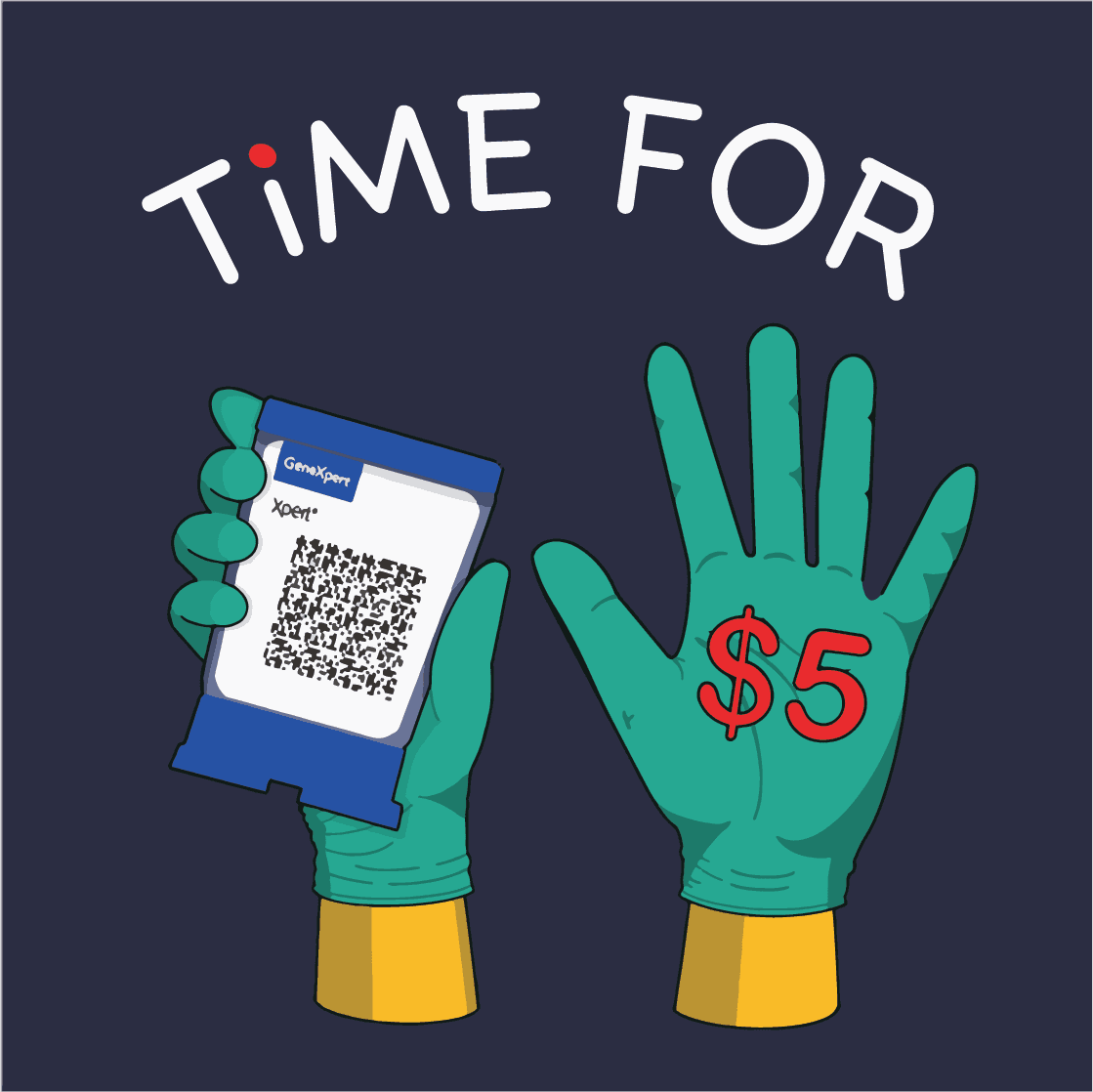

Bring the GeneXpert’s costs down to 5 dollars: new supporting evidence

A recent study by the MSF's Athens Day Care Centre project and LuxOR highlights the importance of affordable Point-of-Care Diagnostics for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections.

MyanmarTestimonies

Q&A with MSF’s project coordinator for northern Rakhine, Nimrat Kaur

Myanmar is facing an acute humanitarian crisis since fighting escalated at the end of October 2023. Nimrat Kaur has been the project coordinator in Maungdaw since mid-April 2023.

Gavi: the future five-year strategy must guarantee equitable access to vaccines

With routine vaccination efforts failing to reach people in fragile and emergency settings, MSF is seeing low vaccination coverage and more outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, like diphtheria and measles